The Burke and Hare murders

In 1828, Edinburgh was a European centre for studying anatomy. Pioneering anatomy teachers taught at the Royal College of Surgeons and dissected bodies during lectures in front of many eager students. However, the strict laws around which bodies could be used led to a shortage. Burke and Hare found a way to earn money from a desperate anatomist in a terrifying chapter of Edinburgh’s history.

A shortage of bodies

Medical training started to become a very popular subject in Edinburgh, thanks to the many experts in the field who taught in the city. Scottish law dictated strict circumstances under which bodies could be used (only those who had died by suicide, in prison or were orphans). This combined with the increased number of students resulted in a shortage. This meant professors and students turned to a solution that was legally a grey area: grave-robbers.

Grave-robbers

While disturbing a grave and selling the belongings of the deceased was illegal, technically stealing a body was not because it wasn’t considered anybody’s property.

The people of Edinburgh were furious about the rise in grave-robbing and even protested in the streets of the city. Guards were hired to keep watch in graveyard and cemeteries installed watchtowers. Some families even paid for large stone slabs to be put over the graves of deceased loved ones until they had decayed past the point that they were useful to anatomists. This high level of vigilance amongst the public made things difficult for grave-diggers.

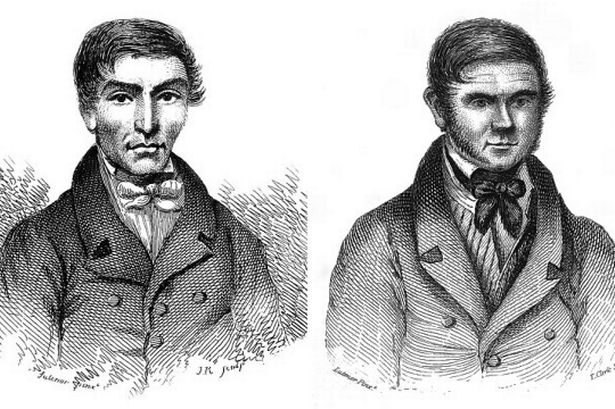

Contrary to popular belief, Burke and Hare were not grave-robbers. Aware that anatomists would pay large sums for bodies, they found another way to get corpses to sell.

The Murder Spree of Burke and Hare

In November 1827, a lodger at William Hare’s house in Edinburgh died while still owing him rent. After complaining to his friend William Burke about the loss of money, they decided to sell his body to an anatomist at the University of Edinburgh. Burke’s testimony claims a student directed them to the residence of Dr Robert Knox on Surgeon’s Square. His testimony also says that, after selling the body, one of Knox’s students told them that if the pair ever needed to get rid of any more bodies, they would be interested in purchasing them.

The order that the murders happened in is not known for certain, with even Burke’s two statements giving different timelines. Hare suffocated the victims while Burke lay across their stomach to prevent resistance. This meant the body did not show any signs that made it obvious the person had been murdered. Their victims included lodgers at Hare’s property in Tanner Close (only a short walk from The Real Mary King’s Close), a salt seller and a woman Burke met in a tavern.

At least sixteen people were killed by the two men.

Discover more of Edinburgh’s hidden history in our other blogs.

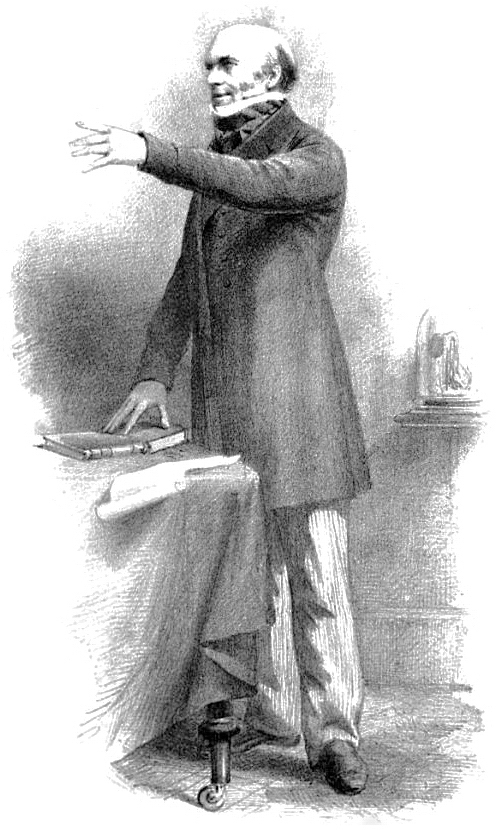

Arrest, Trial and Execution of Burke and Hare

A warrant was issued for the detention of Burke, Hare and their wives on the 3rd November 1828. Hare was offered immunity if he provided the details necessary to convict Burke. He agreed to the deal. He could also not be brought to testify against his wife, so she was also immune from prosecution.

Dr Knox was questioned though it was decided he had not broken any laws. Public opinion, however, was strongly against him. Edinburgh newspapers published editorials accusing him of encouraging the murders. His career was ruined.

On Christmas Day 1828, Burke was sentenced to death. The judge added that his body was to be dissected and, if it became possible to preserve skeletons, Burke’s should be. It was decided there was not enough evidence to convict his wife.

Burke made a second confession in January 1829 where he blamed Hare for the murders. Despite this, he was executed later that month. The crowd who gathered to watch was thought to be as large as 25,000. More students arrived to see the dissection of his body than had tickets and the police had to be called to control the agitated crowd. His skeleton was given to Edinburgh Medical School, where it still remains.

What happened to Hare after he left prison is a mystery.

Step down into Edinburgh’s hidden history with a visit to The Real Mary King’s Close. Explore a labyrinth of well-preserved 17th Century alleys and houses. Book now: https://bookings.realmarykingsclose.com/book